It’s probably just my Instagram feed but I feel like there is a lot of attention on things like technique and different kinds of programing and how they are going to get you injured or how they increase the chances of you getting injured. But if you understand the general mechanisms of injury in strength sports then you know that these factors are likely noise vs the important aspects of the total picture. Before you continue and read the rest of this article here are some questions you can answer to yourself.

Here are some screening questions

- Do you train to improve?

- Do you have goals like numbers on the bar or championships you want to win?

- Do you take training seriously?

If you answered yes to one or all of the above questions then I can give you an estimation with about 99.9% certainty of coming true that you are going to get injured. If you compete in a sport like weightlifting, powerlifting or individual, non change of direction, non contact sports like running or swimming than your injury is highly likely to be overuse in nature. If you play a sport where you change direction, sprint at maximal velocities, strongman, crossfit, or contact then you are going to expose yourself to the chances of traumatic injury as well as overuse injury ????

If you want to get better you need to provide sufficient stress or overload for your fitness to improve as you adapt to your training and competition load/schedule. Anyone who tells you that they can show you how to train pain free or how to reduce or eliminate injury risk above and beyond just not being a fucking idiot with your training program than they are selling you bullshit.

If you want to get better you have to expose yourself to the risk of injury. That’s her boys pack it up, that’s the show.

Injury Risk

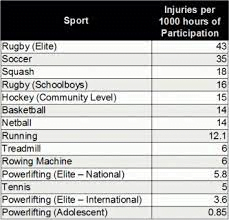

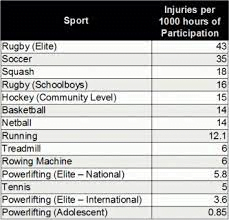

Some activities and sports are inherently more risky than others. Rugby is the ideal game if you want to get injured. There is change of direction, high intensity efforts, contact and unexpected scenarios where someone can come out of nowhere and fuck your shit up without you even knowing about it. American football might be even better as the rules allow players to become human missiles and there is no real line of scrimmage or contact so when open play starts someone can light your ass up from any which way.

I am going to now split off from other sports and speak directly to strength sport athletes as that is the primary focus of this blog. Crossfit and Strongman you follow the same rules with the slight caveat that there is more novelty and extrinsic factors in your training and competition so it’s possible to program sensibly with good thought out limits and rate of gain and still slip on a wet bit of ground and fuck your shit up. It doesn’t matter what sport you do there is an outside chance of injury at all times the risk is never zero.

Even if you don’t train to get better, if you only do yoga and some chilled exercise classes the risk of injury is there.

There. Is. Nothing. You. Can. Do. To. Avoid. Pain. Or. Injury.

Now that we have the caveat out of the way let’s talk about what is within our control and the things we can do to help us get better in a sandbox. Programing and training in a way that lets us see the bus coming for us down the street and gives us enough time to change direction before we get slapped upside the head.

Novelty as a risk factor

We develop specific fitness and robustness towards the things we do on a regular basis. If you have been deadlifting with a rounded back for the last 10 years and you’ve never had back pain you are probably very strong and robust in those positions since you are used to them, have been exposed to them and your body has built up the strength to be able to perform high intensity lifts in those positions.

If you have bought into the neutral spine meme and have been lifting with “perfect technique” for years on end, chances are the second you fall out of position in a heavy lift there is a high likelihood you will pussy out and drop it or if you push through it your brain/body might hit the panic button and you might go into full on back pain meme.

“Biosocial model of pain a quick interlude

One of my athletes/friends Ali is a physiotherapist. I have been training with Ali for about 13-14 years now and since he became a Physio and become more confident in his practices he has taught me a lot about injury and more current learning on the topic. If you are looking for materials barbell medicine are pretty much guaranteed to have some really good work on the topic of the biosocial model of pain response. But it has huge implications for your thinking around pain/injury and your response to it. It’s not a panaceea it’s still messy business but it does give the whole process a lot of lateral movement that can make recovery quicker and your ability to not be cowed by the perceived risk by informing your thinking and beliefs.”

The fact that something is new to you if it’s higher sets, higher RPEs, higher frequency, new exercises, new tempos whatever the variable is if it’s new to you then the risk of something going awry is instantly much greater and you should treat it as such. Something that Tim Gabbett was popuarlising/publishing on when I was still working in pro sport was the concept of the chronic work ratio. Now this model is only really relevant in sports where they actually train a lot like rugby, GAA, MMA etc. In the sport of powerlifting where you would be lucky to do 60-70 mins of actual training in a week we don’t really have enough of a chronic workload for it to be relevant but the concept is still a useful framework to understand the effect of novelty and injury risk.

High training loads don’t increase your risk of injury, Low training loads don’t increase your risk of injury. Rushing into something you haven’t adapted to is one sure fire way to increase your risk of injury. As you can see from the training dose doing less will also increase your risk of injury especially if you are still competing on a semi regular basis since you will reduce your fitness and as soon as your fitness levels drop below the demands of the sport then you are pretty much on a one way ticket to snap city. The opposite is true as well if you increase your training demands too fast to levels your fitness can’t deal with guess what happens? Snap city.

ItS a LoAd MaNgEmAnT iSsUe

I don’t know if me entering into professional sport in 2013 was when physios began to catch on that programing exercise was an important risk factor in injury or if that’s when the first time I came into contact with physios who where switched on enough to actually realise that the program or how we get to the program is a risk factor but it’s been a thorn in my side ever since.

I have sent many an athlete to a physio because we have picked up a niggle or injury in training that needs an outside opinion and I’m pretty sure not once have they asked to see their weights log. But more than once they have come back with load management being the culprit. There is another name for the load management it’s called the program. And chances are that they have come to this niggle from some factor outwidth or something we have missed.

A recent niggle from a lifter came from deep squats and their glute/adductor. Ad Hoc where the issue or management mistake came from was pushing performance on a novel lift too aggressively. The lifter was using deep squats with no supportive equipment (belt and sleeves) as a way to increase their ROM and muscular demands of the movement to help drive adaptation without having to use higher loads. We were directly post competition that we have been training hard into so there needed to be some kind of unloading/novelty in the program both to try and combat monotony but also to give the athlete a mental break from heavy/hard focused preparation.

Well our intervention to help prevent perceived stagnation/injury risk was our down fall. On nearly the last week of the phase of training the athlete picked up a niggle/pain in the deep portion of the squat (which is pretty key for an IPF powerlifter) we have troubleshooted the injury with the help of an initial physio consult and hopefully are on the right path in the lead into competition.

But it was an interplay between the novelty of excessive depth, lack of external support and rate of gain that ultimately led to whatever the overuse/issue was. If we had backed off the directly aggravating factors earlier and worked around it we would have probably got resolution sooner the thought processes at every stage have been logical given evidence and beliefs at the time but we can definitely manage a niggle like that better in the future.

We can have a good chance of singling out the risk factor or steps that may have contributed to the overload issue ad hoc but for every issue you get with one athlete you could have 8 or 10 do the same loading protocol and have zero issues.

The point being it is indeed a load management issue but I don’t know how you can determine that with out looking at the loading….

Injuries are a great point of inflection to identify a risk factor you got blind sided by and to have protocols to preempt them popping up in the future.

Rate of gain as a risk factor

Getting too good too fast is definitely a risk factor when it comes to injury. The common example of this are athletes who use steroids getting torn muscles as their muscles are on a steep path upwards in terms of force production but their ligaments, tendons and bones just can’t adapt as quickly to the stress being applied to them and eventually there comes a moment when the force demands placed on the muscle exceeds the capacity of a ligament or tendon to remain anchored and then it leaves the chat.

How quickly you are getting better/stronger is probably a direct corollary to the the risk you are taking in terms of injury risk. A program such as smolov can seriously give your squat numbers a shot in the arm but the chance you will pick up an injury doing such a loading protocol is massively increased. With great gains comes greater risk.

Gain is not linear, periods of detraining caused by life, injury or deliberate will lead to periods where you get worse either intentionally or from external influence but it will happen to all of us. These periods of training break the linear progress. But while we are in a spot where there is a pattern of gain we make decisions either in the moment (sessions where we feel good and load the bar up and maybe overshoot) or premediated where we put excess pressure on ourselves to get better either throwing the kitchen sink at a weak lift or doing something daft like deliberate over reach into an important competition to get a bounce in our performance. Each one of these actions increases your risk profile and can be managed.

Going full send for a massive PB has big benefits for confidence and progress but if we don’t adapt our subsequent training to take that into the account the extra fatigue acquired places us at increased risk.

Deliberate over reach can be worth the risk for a performance we want to achieve but it should be an informed risk and the training out the other end should reflect this and maybe even plan a period of deliberate detraining.

Rate of gain is your appetite for risk essentially. Is it worth it?

The best injury prevention technique is to be in shape.

Without question the best way to prevent or to reduce the risk of injury is to simply be in great shape. The better conditioned you are for the demands of your training and competition the less likely you are to get injured. If you look at the literature on risk of injury and corollaries almost all of them boil down to how well prepared athletes are systemically (how fit they are) and how prepared they are acutely (how fatigued or fresh they are).

Things that have been shown to reduce injury risk

- Strength

- Aerobic Fitness

- Muscular Endurance

- Balance

- Sprint Speed

- Lower body power

- Flexibility

Things that have been shown to increase injury risk

- Higher than normal training loads

- Bad/Low sleep

- Periods of higher than normal training in high heart rate zones

- Having poor measures on the above fitness attributes

I could go on listing but it is to just illustrate a point you can reduce your injury risk by increasing your fitness/conditioning for the training and sport you want to compete in and your can increase your injury risk by reducing your fitness by working too hard/harder than normal, compromising your recovery or trying to perform high intensity or high output sessions/tasts while you are otherwise compromised.

And to come full circle and finish this article before I write another 2000 words banging the same drum your best injury insurance policy is to work on your training.

- Find a workload that is good for you at the moment

- Progress at a rate that is sustainable and appropriate

- When you find aspects of training you are struggling with then address them by adapting or adding in training that works on your weakness.

- Work on your lifestyle factors and try to provide as optimal an environment as you find sustainable and tolerable.

- Expend your mental capital getting better at these 4 aspects of training and stop worrying about injury or the perceived risk.

- When you get injured, revisit stage one and work your way back up.

Marc

Useful reading –

https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Fulltext/2017/11000/Systematic_Review_of_the_Association_Between.30.aspx

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29239989/

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Systematic-Review-of-the-Association-Between-and-Lisman-Motte/4567f97e7155a74df992561e58c23e687ca2ed85