Well ladies and gentlemen it’s been a while since I penned an article (last one I published was July 2022) it’s something I should really keep at because it really helps me structure my thoughts and I think it actually has a material impact on me as a coach (for the better hopefully). It’s currently 2 degrees in the garage and I can see my breath as I type it doesn’t really make for nimble figures. In an attempt to get something out in a reasonable amount of time I have gone for the click bait list article. However I think this one will be both succinct (p.s. it took 6 days to complete and wound up being 2800 words) and useful, both things I believe my reader shall appreciate and without further ado let’s get on with it.

1 – Stop seeking opinions online

There is a period as a lifter or when you are new at something when seeking out opinions is probably the best thing you can do to get started. However the time frame for this is pretty limited in my opinion you very quickly get trapped in the paralysis by analysis and on the fast road to no where. When it comes to learning the basics and improving as a lifter you first need to establish the lie of the land/find your footing. But as soon as you have an idea of what you are doing/what you are trying to achieve you then need to transition to having a direction and purpose.

The problem with most self taught lifters and why most of them end up quitting or going nowhere with is that they never stop looking at the map or buying new ones. At some point you need to put the fucking paper down and start walking. Sure you might walk in the wrong direction for a while but at least you will be walking. This is probably the biggest benefit to hiring a coach or guide. They already know the best way or at least they know a few ways to the destination.

If you find a coach/trainer online who you like and what they say makes sense consider getting around 80-90% of your training information from them for a good period of time or even better yet once you have a general idea of what you are doing the stop watching youtubers, stop reading articles and stop spending more time on lifting sub reddits than you actually spend training.

2 – Start tracking RPEs or Bar speed.

Autoregulation isn’t a new concept, I was trying to get funding to do a PHD on it in 2010-2011 (closest I got was dear john letter from University of Edinburgh after an interview RIP), Mike Tuchscherer of Reactive training systems has been banging the drum for bottom up programing and self developing training since as long as I can remember certainly from 2008-2009 anyway.

People are skeptical of RPEs for pretty low lying fruit reasons the most common issue is that it isn’t objective and that lifters can’t be trusted and for the most part it’s pretty well founded skepticism from a purely surface level analysis. Experienced lifters already make 100s of adjustments on the fly. They tweak their warm ups, take a bit more time to get ready, change their jumps, Increase the weight if they are feeling good and take the weight down if they are feeling shit.

RPEs are a validated internal measure to track levels of intensity when it is the lifter rating their own performance. It takes a bit of time, calibration and honesty from the lifter’s point of view but taking time to understand what actually is a maximal effort, is in its own right an incredibly valuable time spent. One of the biggest issues novices and intermediates who don’t train around other lifters or with a coach is that they actually have no idea what a maximal effort feels like. Most new or less experienced lifters will simply give up at a point when it feels hard enough when in reality they might have another 40-50% to give.

A common tactic I use with new lifters on a program is to put rep out sets with a spotter in the program for a few weeks or a more recent addition is a call out set where a lifter will guess when they have 1-2 reps left and then rep out. The call out sets could have a bit of self determinism about them that could spoil their applicability but getting new lifters to rep out under pressure is a huge easy win. A common cycle I use is

5×5 @ 75% – rep out last set (10 rep parity)

5×4 @ 80% – rep out last set (7 rep parity)

5×3 @ 85% – rep out last set (5 rep parity)

It is common for lifters to get 13-16 reps on week one and to continue on to overshoot parity by 30-50% which shows that they are holding back because they have no idea what 100% feels like.

Bar speed velocity is definitely a better measure IMO because it does away with intrinsic and extrinsic factors. You do sets/reps and the numbers let you know how you did. It can also be a great tool for increasing intentionality. Reading out bar speeds can REALLY push people to try and move that fucking weight.

Increasing an athlete’s knowledge of performance and also their intention and compensatory acceleration effort.

The only real barrier to entry is that the best/cheapest linear transducer on the market is still the cost of a good barbell at 400-450£.

3 – Keep a detailed training log

This is one of the first bits of advice that you often get offered as a beginner and it is probably one of the best bits of advice you will receive. Beginners get told to keep a journal or log so they can look back a week and see what they did in the same workout so they can try and beat their last performance.

When it comes to programming what a good coach will do is look at your training logs with a fine tooth comb to try and find some threads of information to see the kinds of training you respond best to. They might try running training blocks for longer to see if you keep getting stronger. They might ramp the RPEs or % quickly to see if you respond well to it, they might keep the RPE the same and not nudge you to put the weight up to see how you respond to it. A coach who is good at programming will be constantly tinkering with your training but not in an obvious or wholesale way and they will be looking through your logs closely.

As a self coached lifter you don’t have to become as good as the best powerlifting coaches when it comes to programming but you don’t have the luxury of not being able to set out programs because after all you are designating yourself as your own coach. Point one gives you the germination of this process by curating your online information or your inflows (sYsTeMaTiC bOiZ) to one or at most two people/sources you will reduce the noise drastically.

Then from keeping detailed logs you will start to see patterns of response

- I notice I respond really well when the blocks have more frequency

- I notice when we do volume I feel beat up and sore all of the time and struggle to progress

- I feel strongest when we are doing low RPE work

You will pick up trends that will allow you to make more informed choices as someone who is leading their own training. As someone who is self lead using cookie cutter programs will be a great start but as you become more experienced and have a larger training age you should need to start adapting them to suit you instead of you just blindly following the program if you want to progress as a lifter.

4 – Video your heavy sets

Most powerlifters or lifters who are serious about their training video most of their sets, quite a lot of lifters video all of their working sets. Whilst this is definitely a worthwhile thing to do (so worth while it’s on this list) you should pay attention to heavy efforts. Heavy efforts we will define as anything over 85% of projected max or anything that is RPE 8 or above. The reason why I am singling out heavy efforts is because this is where you are going to notice technique breakdown.

An experienced coach with the illusive “coaches eye” aka someone who has watched more lifting than they would care to even think about will be able to pick out good and bad points of a lift at lighter intensities. For example with most beginners I can spot where we need to focus our attention from the empty barbell for the most part. For intermediate lifters who have a good idea of what they are trying to achieve I normally need them to work up a bit heavier to see where they break down. For advanced lifters it can take up until they fail or come close to failure before where they need to focus their attention can make itself known.

As someone who is less attuned to what you are looking for when you see videos, videoing your heavy sets will flag up areas that need attention either in your execution of the skill or where you need to focus your attention on your assistance work. Also if you have the ability, keeping a log of your heavy sets can prove to be massively beneficial longitudinally as well. For example if you have one set of two reps at rpe eight (1×2 @ 8) as your heavy weight set for the block if you video every set but don’t feel confident that upping the weight is the right choice due to the RPE feeling similar week to week you can compare videos of your heavy sets from week one of the block to the rest of the training weeks and see how it looks in terms of execution and bar speed.

Sometimes the best progress a lifter can make with heavier loads or on a block is to improve the execution of the set (better bar speed, more control or better depth in a squat for example) and whilst you can annotate this in your log (and you should annotate it using RPEs and descriptive notes) objective measures are invaluable as they remove some of the human error which is compounded when running your own training. Videoing important or heavy sets week to week is a no brainer.

5 – Realize that the program is not important it’s how you respond to it

The longer you work with athletes and the longer you are involved in strength training the less importance you put on the program because at the end of the day it’s not as important as a lot of the other pieces

- Lifter’s attitude

- Lifer’s attention to detail

- Lifter’s self belief

- Lifter’s ability to humble themselves and make productive choices

- Lifter’s training environment

- The training crew

- Coach’s trust that the athlete will execute the plan

- The lifter’s trust in the plan

- Lifter’s attention to their training log and ability to put the workout into the correct context

Are just a short list of things I think are more important for strength progress than the program the lifter is on. All a program is, is a list of workouts and microcycles that strung together into a month or a few months of training. It’s definitely a piece of the puzzle but there are many equally if not more important pieces of the puzzle.

One thing that coaches and lifters should be constantly looking for are the elements of a program that increase the lifters performance both subjectively and objectively. The more top down form of periodisation practiced and popularized by sport scientists and strength and conditioning coaches assumes a huge physiological base for its efficacy. However the new forms of bottom up or observation lead periodisation typified by Mike Tuchscherer’s emerging strategies approach gives us a window into the more messy side of things. There is a conflagration of science and experienced revelation building in the coaching, physiotherapy and sports science world. A lot of the old “hard science” first principles are proving to be castles with their foundations laid in sand.

Humans are insanely complex and irrational creatures to assume that our psychology, social setting and environment doesn’t have a real and measurable influence on our outcomes is naïve at best and actively disingenuous at worst. Older styles of programs normally built around a coach or a “method” have their roots firmly in the world of block periodization and the insight of sports science thought leaders like Dr Mike Stone. There is a lot of merit in these approaches and they have measurable and real outcomes however they treat humans as machines, biological specimens that respond predictably to inputs. That is their biggest weakness.

Whilst physiotherapy is decades behind in exercise science and application when compared to strength and conditioning, they are decades ahead when it comes to treating humans as what they are humans and not machines. They have psychological and social factors worked into their modeling in the form of the bio-social model which takes into account the patient’s mental state and their social settings as they real and measurable affects on outcomes. These are factors that aren’t even on the map for strength and conditioning (or at least when I was last actively engaged in reading the scientific output in the field which was probably 3-4 years ago now).

The “individual” response to exercise observed in the likes of reactive training systems’ approaches is real and measurable. Any coach who pays attention to their lifter’s training will see this play out in the real world. However I don’t believe it has it’s grounding in physiological response. I don’t believe the physiological response to exercise to be so wildly variable, if anything it will probably be the opposite. What I believe is that bottom up approaches allow the lifter’s preferences to become apparent at that time which allows them to get into a training flow state where they feel more engaged and motivated (which is termed as momentum in common lifter speak) and this is where the underlying mechanism of cause is coming from.

I believe both schools of thought have merit and the best way of programing is to use both styles. There is merit to a top down, physiological response lead approach but this needs to be informed by a systematic process that allows the program to wrap around the individual and not the other way around. As a self taught lifter you can latch onto the programing work of others but use paramaters like RPE targets for weeks, length or progressions, number of working sets, number of exercises. Things that can be tweaked from block to block to see what you prefer or “respond to” best.

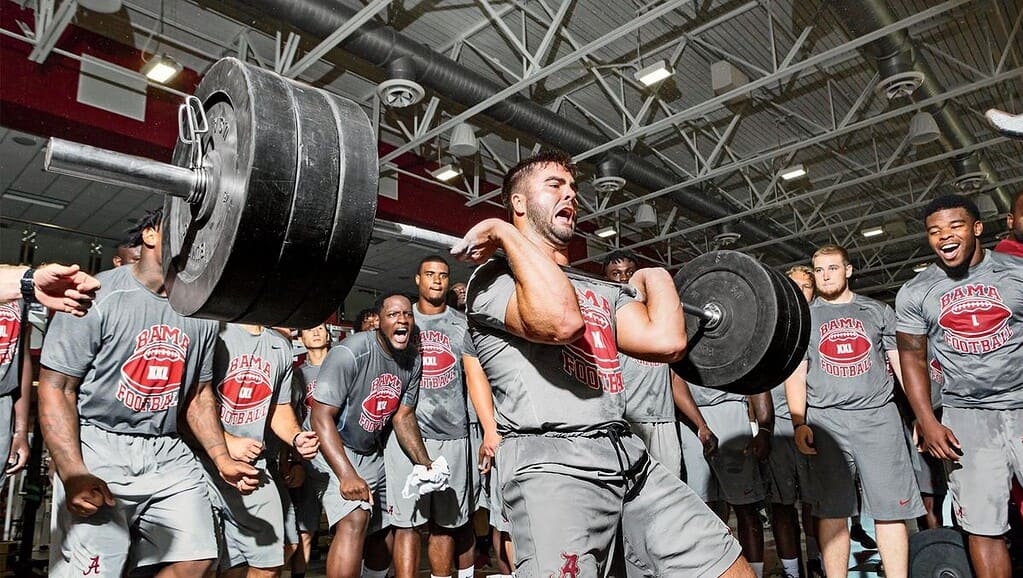

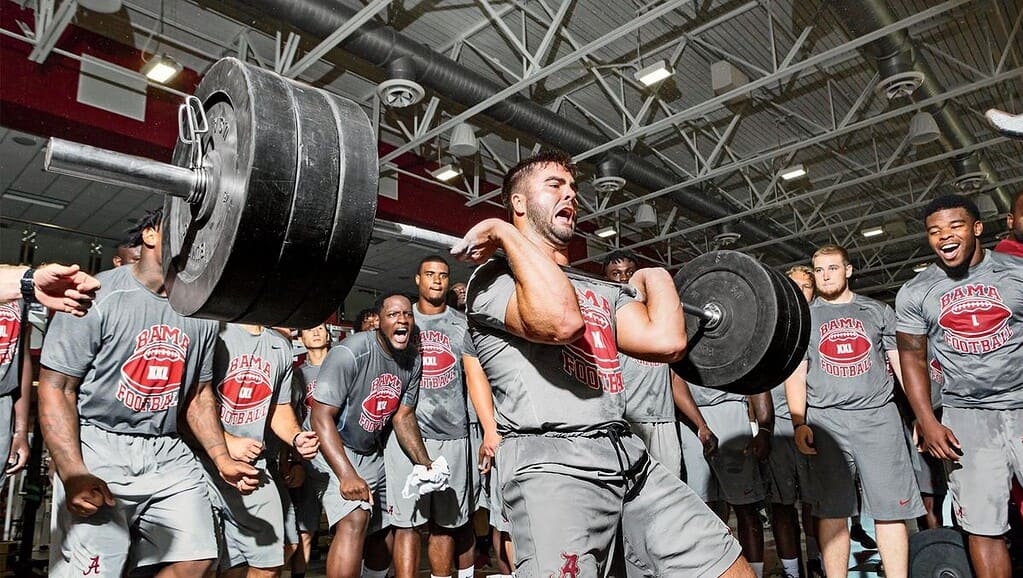

6 – Train in a gym with other lifters

Finally if you are a self lead or trained lifter this point really can’t be stressed hard enough, I didn’t include it in my original five because it’s not feasible for a lot of people to train with other lifters or to gain access to a gym with other lifters however if it is in your capacity to do so I would strongly advise you go out of your way to make it happen. There are so many positives to training in a group in a sport like powerlifting ESPECIALLY if you are self coached one of the biggest negatives to being a self coached lifter is living in the echo chamber of your own head.

Hanging around other lifters who are doing their own thing or have a coach can be a great avenue for ideas. It is also a great sounding board for ideas and training concepts not all of your training partners will provide you with useful insight but even the act of talking out loud and discussing various things can be invaluable for idea forming and even better if you get into some form of push back or debate.

Having other people with eyes on your technique can be invaluable for catching small things you don’t pick up on video or being around lifters who are around the same level or stronger will really give an edge to training especially if you are of the competitive mind set. Even helping out beginners can really help your own progress as you need to crystallize things around technique and general programing if you are going to communicate them to others.

Considering lifting is on the face of it an individual pursuit their really can’t be an over exaggeration to how much better it is in a crew or team.

Hopefully you have picked up some useful ideas you can use to improve as a self coached lifter or you can quit the bull shit and

Work with us in person

Work with us online

Marc